In a planetary gear — or epicyclic gearing — at least two, or often more, planetary gear wheels run in a ring gear. All planets are connected to one another via the “sun,” a central gear wheel. This compact arrangement transmits torques in applications where there is little space available. With the right design tricks, you can get a lot more out of planetary gears.

Stefan Fischer develops planetary gears for industrial drive technology at ebm-papst in Lauf. (Photo: ebm-papst)

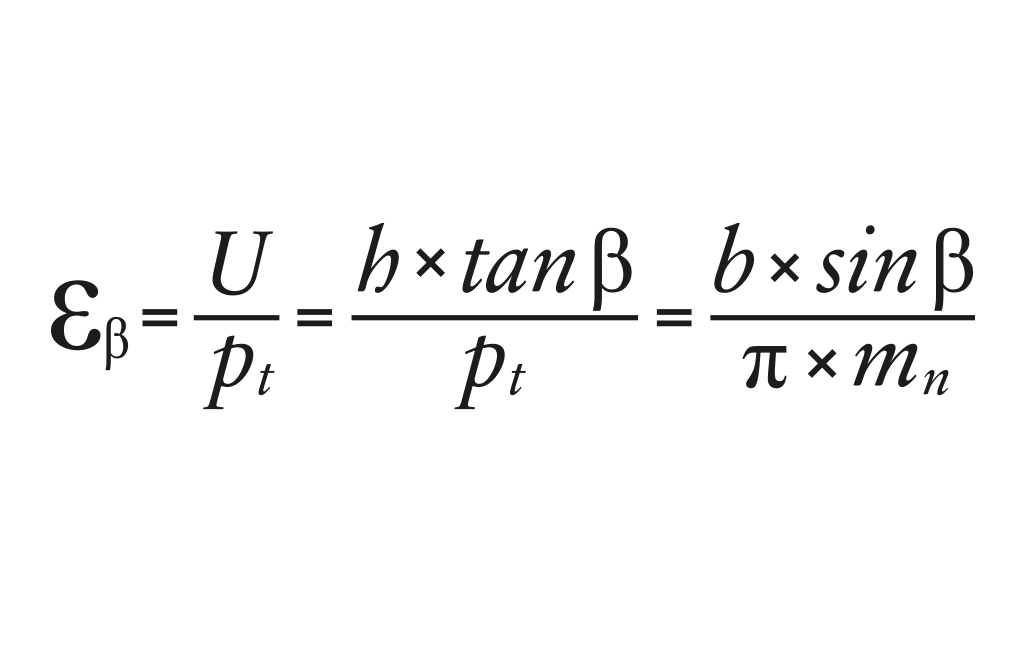

An important starting point is the helix angle β on the gearwheels. If the wheels are straight toothed, it is technically difficult to always have a tooth meshing when there are high transmission ratios. This means that the transmission vibrates, is loud and wears faster. Therefore, it is good to design the teeth at an angle and achieve an overlap ratio. Although this is technically challenging, it is rewarded with a smooth operation with low noise and low wear.

The overlap ratio εβ can be tinkered with. With some of our transmissions, we have optimized the helix angle β with a seemingly paradoxical result: although our sun only has three teeth, every planet has 2.049 teeth meshing at all times, i.e. on three planets, this is a total of 6.147 teeth.

In addition to even quieter operation, we achieve one thing above all else: compactness. This means that we can manage with fewer transmission stages one after the other. For a reduction ratio of 17 : 1, we need just one gear stage instead of the usual two; for a reduction ratio of 204 : 1, two stages suffice instead of three — always one stage less than usual. This greatly reduces the overall length of the transmission.

The overlap ratio is an important factor for planetary gears. Although the sun (a) only has three teeth, there are always 2.049 teeth meshing simultaneously on each of the three planets (b). The optimally selected helix angle β makes this possible.

Leave a comment