Geoff Barker turns the tap and smiles. Not just because there is warm water coming from the tap. You’d expect that from any new boiler. He’s smiling because he knows he’s saving money. From the outside, the compact device hanging on Barker’s wall does not look any different to a normal gas boiler. It saves space and generates heat for water and central heating. But it also generates electricity. This kind of simple micro combined heat and power unit (short:micro-CHP unit) is the first of its kind.

The little magic box, from the Flowgroup in Chester in north-west England, has been available since the start of the year on the British market under the name Flow, intended for larger households. If Barker were a normal customer, he wouldn’t even have to pay for the unit. The deal works as follows: anyone wishing to purchase the Flow only has to pay the installation costs. They also take out finance for the cost of the Flow and signup to Flowgroup for their electricity and gas. After this, the customer receives a rebate through their energy bill to cover the cost of the finance, all made possible by the local low cost electricity generation. After five years, the Flow has paid for itself and the electricity produced results in energy savings for the owner.

From start-up to success

Barker isn’t a normal customer, however, the device on his wall is only for test purposes. He is Business Development Director at Flowgroup and was involved in the development of the Flow from the beginning. Getting the product ready for full production was a long journey. The business began in 1998 with the business model of developing new energy technologies and then selling them to other companies.

The Flow’s story begins in 2006. “Originally, we just wanted to develop new, cost-effective technology for a micro-CHP unit, which we then wanted to sell to heating appliance manufacturers. But during the development process, we decided to take full control of the production and marketing”, explains Barker. This was no small venture for a company that had never built a boiler itself before. Even the technology it was based on had never been used in this form.

The boiler takes up little space in the home.

The inverted refrigerator

The technology is similar to a cooling cycle in a refrigerator, which obviously has little to do with a gas boiler. One aims to remove heat while the other has to generate as much of it as possible. The designers turned the cycle principle on its head and the Flow boiler now works in precisely the reverse manner with the so-called Organic Rankine cycle. This process has previously been used in geothermal or solar power facilities. Other manufacturers use expensive solutions in these devices like Stirling engines or fuel cells.

“During development, we decided to take production and marketing into our own hands.”

Geoff Barker, Business Development Director at Flowgroup

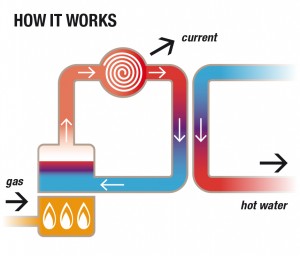

By contrast, the Flow essentially functions like a normal gas condensing boiler, except that instead of water, the combustion heat evaporates a special fluid with a low boiling point. This fluid is similar to the cooling fluid in a refrigerator. The vapor that this creates drives a scroll, which acts like a mini generator and produces electricity. Once the vapor has fulfilled this task, it enters a heat exchanger where it heats the water. The vapor condenses back to a liquid and the cycle can begin again. A pump keeps it moving through the system.

That’s the theory. In practical terms, this meant a lot of development work. “Most of the work went into developing the pump, which is the key component for the cycle”, explains Barker. This is because the pressure and the speed at which the pump drives the fluid are decisive for the Flow’s performance. The motor for the pump must be able to cope with high and low pressures, without heating up too much. As the boiling point of the fluid is very low, the motor cannot heat it up too strongly, as the vapor bubbles created would damage the pump.

Expertise from the continent

At around the same time, the engineers at ebm-papst in Landshut were working on a new motor for fans. When Paul Prescod, Commercial Director at ebm-papst Automotive & Drives UK, found out about this project at a presentation, he immediately thought of the drive for the pump which the engineers at Flowgroup had asked him about. “The motor from Landshut may not have been developed for this kind of application, but its characteristics were a pretty good fit to the requirements”, remembers Prescod.

Working closely: Geoff Barker (middle) discussing motors and fans with Paul Prescod (right) and Steve Durant from ebm-papst UK.

His colleagues in Landshut were quickly convinced and produced a prototype of the motor, which would later be launched on the market as the BG43. The EC motor was an instant hit. “It was exactly what we were looking for: a highly efficient and compact motor”, says Barker. It was the beginning of an intensive cooperation. “We developed many different prototypes of the Flow and ebm-papst supported us in every new development step with their expertise”, explains Barker. In the end, an Italian company was chosen to produce the pump. “As we are also active in Italy, we were able to go along with this step with no problems and support the work there, too”, emphasises Christian Diegritz, Head of Sales Department at the Landshut plant.

The plant gave the development of the project significant support. But this support was not just limited to the motor. Flowgroup also chose to use the NRG 118 blower from ebm-papst. That was music to the ears of Steve Durant, Senior Consultant at ebm-papst UK, who was responsible for this component. “We were now able to offer the motor and blower in a single package, which further reduced the costs for the Flow.” No small matter when you remember that the Flow aims to be an affordable solution.

A clever business idea

After countless tests and certifications, the micro-CHP unit kept making progress. In 2013, the question for Flowgroup was how to best get the mini power station into households. The slightly unusual answer was to use their own energy company. “We founded a subsidiary which provides customers with gas and electricity. This gave us a customer base to act as potential buyers of the Flow”, says Barker of his somewhat different business idea. Customers will be able to profit from this from early 2015 in a range of ways.

The device is compact and easy to install. “We designed the Flow so that it could be installed on the wall by heating specialists with minimal training”, explains Barker. Here, it produces around 2,000 kilowatt hours of electricity in addition to heat. This corresponds to half the consumption of an average British household. Once the Flow has paid for itself after five years, the consumer therefore saves around 50 percent of their electricity bill. The Flow is currently only available in Great Britain. “We are already in talks with energy companies in other countries to introduce the micro-CHP unit there”, says Barker.

Smart electricity

The gas-fired combustion chamber heats a special liquid comparable with the refrigerant in a refrigerator.

The gas-fired combustion chamber heats a special liquid comparable with the refrigerant in a refrigerator.

The resulting steam drives a generator that produces electricity. Then the hot steam heats water in a heat exchanger and condenses.

The liquid is pumped back to the combustion chamber and the cycle resumes.

Leave a comment